|

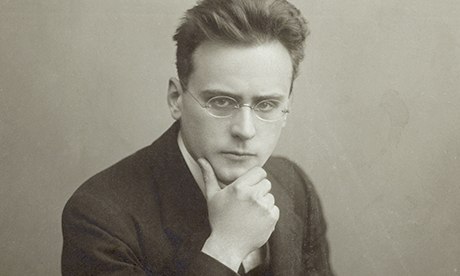

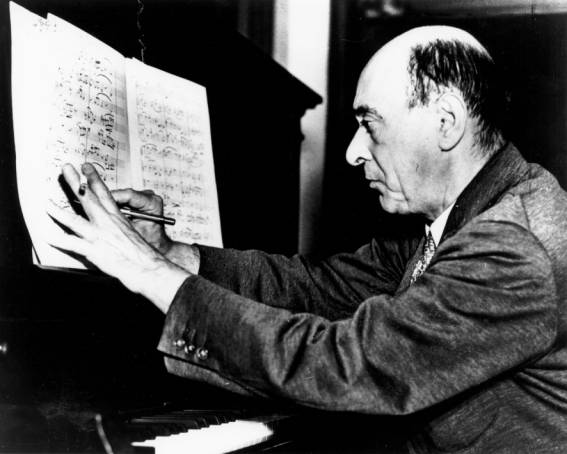

No, it is not just the fabulous hair, stern look, and hip glasses. As I have studied the music and lives of the Second-Viennese-School composers over the past month, I have been pleasantly surprised by a few discoveries. The first being: Schoenberg writes expansive and lyrical vocal lines! Listening to his early songs (especially with orchestra) or even his Pelleas und Melisande, one can easily mistake the work for that of Richard Strauss. The sweep, the grandness, and the (heavy) orchestration all speak to the links between Schoenberg/Strauss and Wagner/Beethoven, the apparent, direct lineage. This week, I have been focussing on Webern, however: reading the 800-page biography by Hans Moldenhauer. (Quite the tome to tote around. And I have been accused of reading a Harry Potter book. Excusez-moi?) As it turns out, Webern's experiences (and travails) as a composer, seem to mirror my own. And , while I am struggling at the moment to keep myself positive with regard to a career in composition and forcing myself to acknowledge the bigger picture rather than fretting over minutiae, I take comfort in the fact that another composer, whose music I revere, struggled as much. Below are some quotes and interesting parallels between our lives: First, Webern issues the same complaint in 1902 that I hear many of my colleagues declare today: "Now the concert season roars with terrible force! Mostly miserable programmes [sic]! Every concert over-crowded with people who applaud after each number, not caring whether it is good or bad. Probably, nay certainly, the people can no longer perceive any difference. Their taste is continually corrupted by miserable programmes and witchcraft virtuosi." Ok, I definitely felt this at a recent concert that I thought was good, but did not warrant the sudden, almost violent, thrust to a standing ovation (those older patrons are surprisingly agile) at the end of every piece. I feel no obligation to stand - and I can withstand glares, from young and old, so save them for someone else. Now, who knew that Webern worked in the theatre? Not I! Here are some of his reflections on these jobs. I've said or thought all of them at one point or another. "My activities have been horrible. I find no words to describe such a theatre. May the world be rid of such trash! What benefit would be done to mankind if all operettas, farces, and folk-plays were destroyed. Then it would no longer occur to anyone that such 'art work' had to be produced at any price. It is enough to drive one mad." PREACH "Mahler remark[ed] that I should not go to theatre since I would not find time to compose. I cannot get this out of my head anymore." Thanks, Gus. Words of wisdom. "I would flee a theatre such as the one where I am at present as if it were a place infested with the plague, and now I myself must help to stir the sauce. Often I am ashamed, I appear to myself like a criminal even collaborating in this hell-hole of mankind. I can hardly await my deliverance from this morass." Speaking of the necessity to work at such jobs while neglecting his writing he said: "I maintain almost unshakably the stand of wanting to dedicate my work exclusively to my compositions. I could entirely forswear every worldly position. If I could only halfway find subsistence in any kind of job that does not take me away from composition, wholly and completely, for months on end. As it is, one must kill off what wants to come forth. This is the difficulty, and it makes me very unhappy." (Disclaimer: This does not reflect my personal feeling about EVERY theatre job I have undertaken. If you are reading this, I am NOT talking about you.)  As I get (ahem) older, I become more and more aware of the gulf between my age (as if I would ever reveal my REAL age) and the ages of my colleagues who are at the same stage in career as I. Here are some of Webern's similar reactions: Regarding Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who shot to stardom at age 13(!): "Publishers, performances–the boy has everything. I will become old before that." Webern was 27 at the time. The next year, while working in the theatre, Webern again felt despondent: "Am I thus to spend all my years–feeling redeemed each evening that another day has passed? Does this make any sense? I am growing old and am nothing and have nothing and accomplish nothing, or better, cannot accomplish anything." Yep, I think I have said something similar weekly for the past...well, a lot of years. I have been entering a TON of contests and commissioning competitions over the past three years. With almost no success. Some second places. Mostly no word at all. They take the $100 entry fee (plus the exorbitant cost to print, bind, and ship a score) and run! Ah well. I'll leave you with Webern's Five Sacred Songs, op. 15, which he sent into the Berkshire Chamber Music Composition Contest in 1924 and LOST! Didn't even place. Who won? I guess that is something to research.

3 Comments

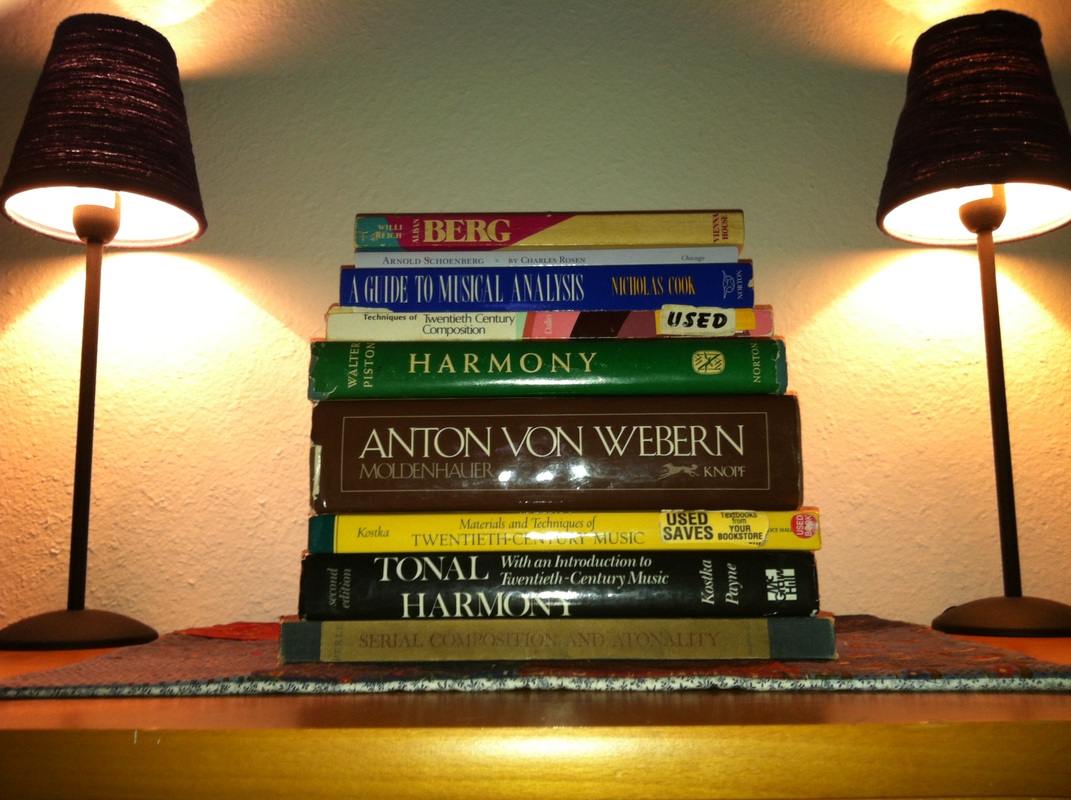

Continuing my study for the month. I have my first comp exam (theory) on April 14th! (Send me some good vibes, please!) And I plan to take a second comp exam in June - so I am double-duty studying! Yay! Actually, I am rather enjoying myself. Going back to the basics, reviewing, and working my way back to and beyond where I am in terms of knowledge is how I like to study. Below is a picture of the books I am reading this month. (Some of which I have read and studied many times before, so stop judging me for these basic theory books - it's called review, ya'll.) Of course, all of this is supplemented with score study and listening. Still delving into the 2nd Viennese School oeuvre. Finished my initial study of Berg. Moved to Schoenberg this week (the order of study was based on when the biographies I ordered came in the mail). Please note, the Charles Rosen book on Schoenberg (under Willi Reich's book on Berg) is 100 pages, while the Anton von Webern bio is almost 800. Oh my. And this week for theory - I need to practice writing fugue expositions again! Gotta go dig out my notes. In order of appearance: Alban Berg - Willi Reich Arnold Schoenberg - Charles Rosen A Guide to Musical Analysis - Nicholas Cook Techniques of Twentieth Century Composition - Leon Dallin Harmony - Walter Piston Anton von Webern - Hans Moldenhauer Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music - Stefan Kostka Tonal Harmony - Stefan Kostka and Dorothy Payne Serial Composition and Atonality - George Perle I'll leave you with three Schoenberg pieces, in which he began to use serial techniques. 5 Pieces for Piano, op. 23 (1920/23) - Considered the first use of serial technique. Without getting into detail, the last movement (the waltz) uses a 12 note motif as the melody, with everything else derived from this "series." Charles Rosen: "There is one revolutionary aspect about this piece...except at the beginning [of the waltz], the order of the twelve notes is not a melody, but a quarry for melodies; the melodic line may at times start in the middle of one presentation of the set and continue part of the way into the next...The phrases are broken without regard to the twelve-note set, which has an identifiable shape of its own only the first time it is played." Serenade, op. 24 (1920-23) - The fourth movement, a Petrarch Sonnet sung by bass-baritone, uses the 12-tone technique. The singer repeats the same set of pitches throughout the piece, but, since the lines of the Sonnet are 11 syllables long, "each successive verse begins one note earlier." This is the longest piece of the three and probably my favorite. I love the instrumentation (Clarinet, Bass Clarinet, Mandoline, Guitar, Violin, Viola, Cello), and the quaintness and character of each movement. Suite for Piano, op. 25 (1921/23) - This piece is definitely serial. Schoenberg uses one set for the entire piece (6 movements), to unify. You can look up the series and its derivations online. Very symmetrical with the use of the tritone, and references Bach's name in the last 4 notes. Pieces like this are when you go: oh, yeah, genius. Please note that in each of these three works, Schoenberg adopts musical forms and genres from the past, as a sort of reference point. Definitely not free-form, "anything goes" works. And also not cold, unfeeling pieces. Character abounds! If one studies these three pieces with the "image" (sound-image? there must be a German word for that) of the older forms (Minuet, Gavotte, etc.) in mind, the fact that they are "freely" atonal or serial feels almost inconsequential. In fact, I find that, free from the constraints of the tonic-dominant relationship and the "tyranny of the octave," as Charles Rosen calls it, the character of each movement (dance form, etc.) comes through with a heightened clarity. (PS - the 5 seconds you have to wait to skip the ad at the beginning is SO worth it - love this recording!) I began studying Schoenberg's vocal music a couple of days ago (again, for a comprehensive exam). Along with lots of listening, score study, and poring over journal articles, I have been reading Charles Rosen's slim volume, Arnold Schoenberg. Here are a few interesting tidbits and insights into one of the most revered and reviled figures of 20th century music composition. Of the string sextet, Verklaerte Nacht, a contemporary of Schoenberg said: "It sounds as if someone had smeared the score of Tristan while it was still wet." Oh my. How about this Richard Strauss v. Schoenberg action: Strauss, 1913: "Only a psychiatrist can help poor Schoenberg now...He would do better to shovel snow instead of scribbling on music paper." Schoenberg on the occasion of Strauss' 50th birthday: "He is no longer of the slightest artistic interest to me, and whatever I may once have learned from him, I am thankful to say I misunderstood." Yikes. Another Strauss TidbiT from Charles Rosen: "Strauss is known to have been disconcerted [haha- good one, Charles] by the growing virtuosity of modern orchestras and their ability to give an unfortunate clarity to passages written to sound as a sweeping and harmonious blur." Reminds me of some of the chorales from Bach's St. Matthew Passion, which would have sounded more dissonant in his tuning system.  by Charles Rosen "A dissonance is any musical sound that must be resolved; a consonance is a musical sound that needs to no resolution." Thanks, Charles.

"If dissonance is understood as that which demands resolution (and this definition must be maintained if the expressive role of dissonance in the language of musical representation is to be understood), if it has meaning only as part of an opposition consonance-dissonance, then the elimination of consonance, of resolution, destroys the basis for expression, makes dissonance itself meaningless. The powerful emotional force of Schoenberg's music would then be intelligible only against an inherited background of traditional harmony, and would itself be an incoherent system, dependent on a musical culture it was intent on destroying." Oh, the irony. More Berg - study, study! As I am writing my own opera (only a 1/2 hour left to complete!), struggling to finish while I daydream about an actual production of the piece, these stories about Berg (all taken from Willi Reich's book Alban Berg) help me to stay focused and hopeful. In 1922, after completing the score for Wozzeck, Berg attempted to sell copies of the vocal score to make some money. The pages of the score numbered 230 and the cost came to 150,000 Austrian Kronen (20 Swiss Francs). Berg sent one of his pupils out with the statement: "Art looks for Bread," soliciting patrons of the arts to buy a copy. "The production [of the score] was enormously expensive and I'll never be able to persuade a publisher to pay for it, so I would like to sell a number of them beforehand for my own account." Self publishing! One of his students said: "No publisher even thought of publishing the monster; the vocal score was in hot demand only amongst his good friends, and they got it free." Oops. In terms of the experience of opera, particularly Wozzeck, Berg believed that the audience should have no idea of form and structure from hearing the piece, rather they should be swept up into the story: "From the moment the curtain rises until it descends for the last time, there must not be anyone in the audience who notices anything of these various fugues and inventions, suite movements and sonata movements, variations and passacaglias. Nobody must be filled with anything else except the idea of the opera–which goes far beyond the individual fate of Wozzeck." Drama, drama, drama! Would Berg have disagreed with the above pre-concert lecture? Hm, I doubt it. Of Bruckner's music (as well as Mahler and Wagner) he said: "Even Bruckner–who had been dead some years–was a long way from being 'generally recognized' or 'arrived' as one calls it. Societies had to be founded to bring his work within reach of the world's understanding. These societies considered it their business to make propaganda, as we call it today: introductory lectures, and performances of his symphonies in four-hand reductions...all this was necessary for Bruckner at the time."  Anton Bruckner (1842-1896) Below is the Wozzeck I am currently listening to - but on LP, yes, a real vinyl recording! Love. Finding a libretto and scene by scene musical analysis is easy online. I think the translation of the German (if you don't speak the language) is especially important to understanding Berg's musical choices. Enjoy! |

Andrew Haile AustinA record of events, a log of compositional progress, Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed