|

If you have been watching Marie Kondo on Netflix, which I assume you have, then you are familiar with her style of organization for our age of consumerism. Maybe you've chuckled a bit when she knelt down to greet the home or when she insists that one must touch every item to "spark joy" and if no such spark occurs one should thank the item before discarding it. Or maybe you have realized that in an age where plastic is destroying the oceans, taking the time to respect and familiarize yourself with every belonging you own is not such a ludicrous idea. After listening to several newish orchestral works (premiered in the last 5 or 6 years), none of which I will name here (you can DM for details, if you are really interested - maybe you'll have a completely different experience with the pieces than I did), I believe we composers can benefit from KonMari. I usually refer to this type of writing as "kitchen sink" composition because everything is crammed into the mix, sometimes in a more artful way than others. So much clutter! Have you touched every note and asked if it sparked joy? (My other least favorite style is "orchestra tuning" music where we are forced to sit through 7 minutes of sliding sonorities and timbral changes.) I have listened to at least five orchestral works this week that use the same formula: 1) provide a hook for the audience. This can manifest itself in several forms: a "jazzy" introduction or conclusion (a concluding hook is especially desirable so everyone can chuckle at the end in the most erudite manner, be in on the joke, and say things like: why does classical music have to be so serious??), a reference to pop culture in some musical form, perhaps littered throughout the piece (if you can quote, Björk, Radiohead, or the Beatles you win), or to cater to the crowd: quotations from other classical works thrown into the last (shortest and fastest) movement as "whimsy" - not to add significance to the piece. 2) no recurring ideas God forbid - are you even creative, bro? 3) no one plays anything similar at the same time If (I stress if) instruments happen to play anything remotely similar at the same time, there must be some metric irregularity. Also, the more notes and varieties of rhythm that can be layered, the better the craftsmanship. Seriously, tuplets, tuplets, and more tuplets. All of these: irrational rhythm or groupings, artificial division or groupings, abnormal divisions, irregular rhythm, gruppetto, extra-metric groupings, or contrametric rhythm (from the Wikipedia article on tuplets!). Odd numbers are best. 11's or 17's? They will definitely be accurately played. 4) every note MUST have some kind of articulation and a dynamic marking. Players cannot be trusted to interpret. Leave nothing to chance! And if an instrument uses vibrato, you should specify when and how that vibrato is used. At all times. Ex. over ONE quarter note: vib.-->non vib.-->quasi vib.--->molto vib --> ord. vib. 5) satire At first, make it seem like you are composing a piece that humorously comments on the more cliché practices of modern composers, then stretch that out for 17 minutes until the audience realizes it has been duped. Just as they begin to despise the piece (and you), add in a non sequitur quotation or "jazzy" section (see no. 1) to gain back their trust. Then, continue what you intended to write. The audience may turn on you again but as long as you end with something tongue and cheek (again see no. 1), no one will mind the 16 minutes of squirming and secretly checking their phones. Ok, enough burning bridges. Why don't you click on these links and see which sparks joy:

1 Comment

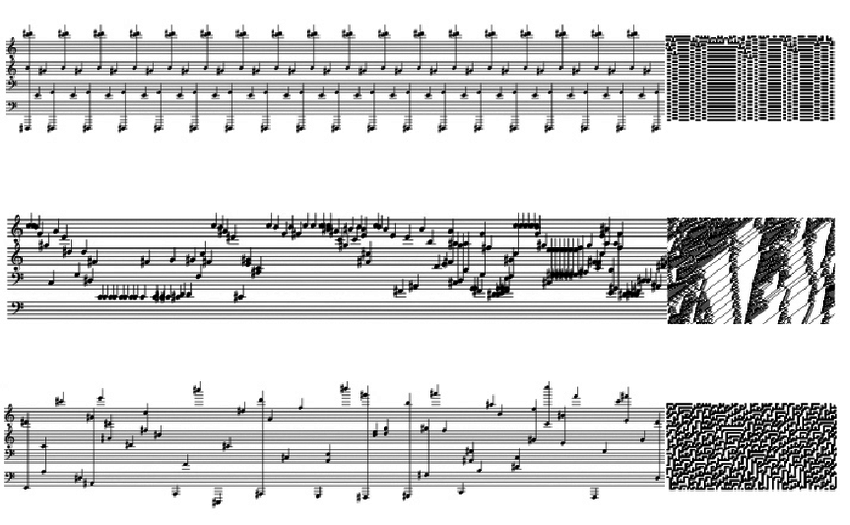

Recently, I have begun going through the archives of Berlin Philharmonic concerts - highly recommended for concerts at home, live or recorded. (www.digitalconcerthall.com/en/news) Mostly I have been exploring the 20th and 21st century repertoire that I don't know with score in hand - a lot of scores are available online through the publishers as perusal scores, some you can even download, which I prefer so I can use them on my iPad. I'm happy to report that the Berlin archives have a healthy amount of rep from the last 100 years and ashamed to admit that I have heard a scant number of what they offer. Putting shame aside, I have in earnest (thank you, New Year's resolutions) set to work listening to/watching a couple of hours worth of these pieces a day. (I should say that I am [for now] skipping over much of the standard rep composers such as Ravel or Shostakovich in favor of getting to know the orchestral music of Chin or Haas better.) I started at the letter "A" on the archive list not only as an admittance of my own quotidian nature but also because two of my favorite composers were included with that letter: Abrahamsen (Three Pieces for Orchestra and Let me tell you) and Adès (Asyla, Powder Her Face: Dances, and Three Studies from Couperin). The A's also contained pieces by Samuel Adler, Julian Anderson, George Antheil, and Richard Ayres (his NONcerto for horn and large orchestra which I skipped because I am in search of a score). After the A's, to reconcile my commonplace alphabetical beginning, I jumped to the Z's. So far at the end of the alphabet, I have been focusing on one composer whose music spoke to me in ways I have not yet begun to articulate: Bernd Alois Zimmermann. Why have I not gotten to know this composer before this year? Too much rep, not enough time. And that is what this trek through the archives is all about. Berlin has six of Zimmermann's works in the archives: Symphony in One Movement, Alagoana, Canto di speranza, Photoptosis, Violin Concerto, and Requiem for a Young Poet. The last piece I have not heard yet because I need to sit in the NYPL reference section in order to listen with the score. Many scores of his work are available through the publisher Schott - if the score has a "Preview" banner on the cover, you can click on it to see (and download for further study) the full score. If I could not find the scores online, I looked for them through the library or interlibrary loan (although most libraries are wont to lend scores out for some reason likely quantified monetarily - insert eye roll emoji ). Today, I listened to (along with Bernstein's Divertimento and Martinu's Violin Concerto no. 1 - see, I'm jumping around the alphabet a bit) two pieces by Zimmermann: Canto di speranza and Photoptosis. In the latter, Photoptosis ("Incidence of Light") , Zimmermann makes use of musical quotation from Beethoven, Bach, Scriabin, Wagner, and Tchaikovsky layered over each other and emerging from a sonorous orchestral texture inspired by an Yves Klein painting for the Gelsenkirchen music theatre. The orchestral representation of light captured by Zimmermann mesmerizes the listener. As conductor Hannu Lintu said: "Zimmermann’s music is exceptionally rich in colour. I can see and hear in it a musical synthesis of colours and lights, like continuing from where the Impressionists and Scriabin left off. Photoptosis is a study of the way sounds and motifs change when they are instrumented in different ways." The quotations feel like a part of the light play, as if one is seeing (hearing) the work from a different angle and a flash of music suddenly appears. (Listen here or buy here) The use of musical quotation reminded me of another piece (not Berio's Sinfonia but good guess, love that piece): Prism by Jacob Druckman. In this three movement work for orchestra, Druckman explores the myth of Jason and Medea as seen through the music of Charpentier (Médée), Cavalli (Il Giasone), and Cherubini (Médée) - looking as Druckman said both forward and backward. In the first movement (Charpentier), the quotations pop up as surprises, leaping into being and playfully usurping command of the piece, if only for a few bars, then disappearing again. The second movement (Cavalli) gives the impression that Medea is a wax figurine melting in front of our eyes (ears). The musical quotations hover in the background, as if heard through a thick, wooden door or floating on the air a great distance away. Cherubini's music confronts the listener in the final movement with violent jabs and caustic taunting. The orchestration of the movement feels more akin to Mahler with massive waves of sound overtaking ones senses between chamber music-like instrumental solos. Allusions to war: guns firing, marching, and brass fanfares abound. (Listen here) Perhaps as Lintu said: "Music [of the late 20th century] was in transition, and the cupboard was bare: composers felt a need to look back over the whole history of music, and especially the stylistic trends of the 20th century – its pared-down, endlessly theorised musical phenomena, modern simply for the sake of it." Both of these works use light as inspiration through which to view the work of other artists - with Zimmermann the lens is more open and the picture blurry while Druckman focuses in on specific subjects. Interestingly, both pieces end abruptly, just as light has no discernible ending point. Below, Druckman discusses his compositional process. I've never worked that way: writing out a few pages of ideas for the instruments I have available and then seeing if any of them connect. Worth a try. I love how he laughs off agonizing over writing. Oh, and the dog story... You can see a perusal score for Prism using the link below. You need Flash, FYI, and cannot download the score.

www.boosey.com/cr/perusals/score?id=1090 NY Times review of Prism here. Also an article on light in Druckman's music here. To see a score for Photoptosis, I borrowed through Interlibrary loan through the New York Public Library. |

Andrew Haile AustinA record of events, a log of compositional progress, Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed