|

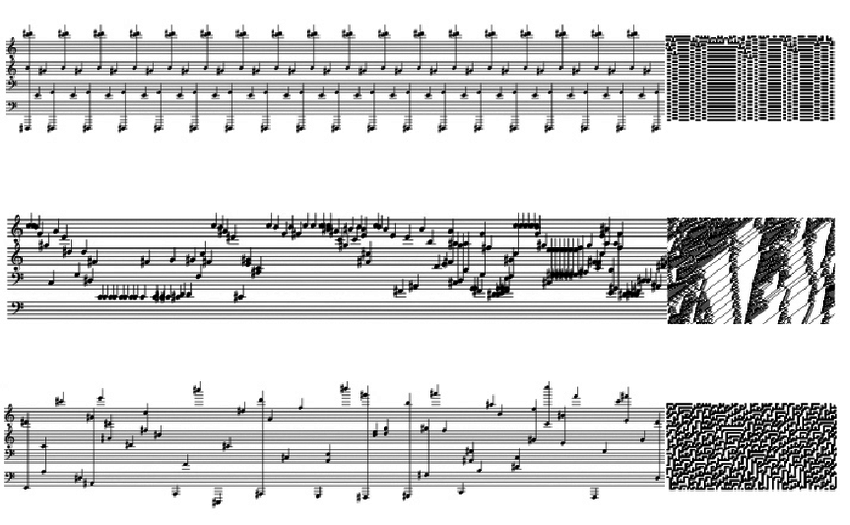

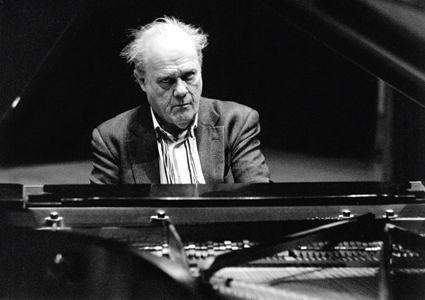

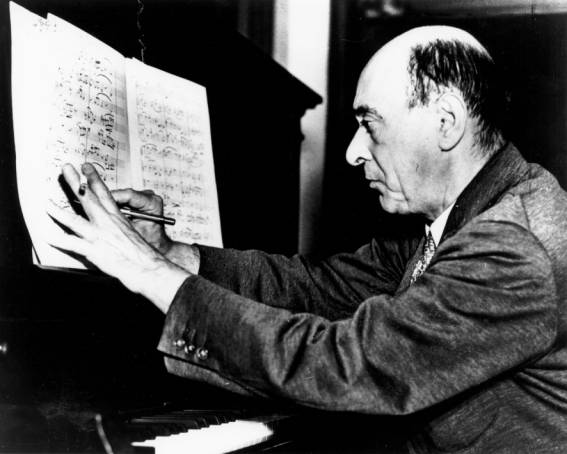

I couldn't resist that smoldering photo. Perfect pic for mo-vember. I'm sure he was 19 or some obscene age then - I never looked like that in my teens haha. I have begun a study of Alan Hovhaness - an American composer of Armenian descent (only relevant because he uses Armenian melodies and techniques in his compositions). Very prolific, he wrote 500+ works - and even burned some of his early work, so who knows how much music he actually composed in his 88 years! I imagine his studio always looked like this: From a NY Times article by Mac Randall May 20, 2001: "Hovhaness -- born Alan Vaness Chakmakjian in 1911 in Somerville, Mass., to an Armenian father and a mother of Scottish descent -- produced perhaps the largest individual catalog in 20th-century music. Officially, he wrote almost 500 pieces, the best known probably being his Symphony No. 2 (''Mysterious Mountain'') of 1955. But that tally does not include the thousand or so early works he is said to have burned in a cathartic mid-1940's bonfire. Nor does it include the compositions his widow, Hinako Fujihara Hovhaness, continues to discover among the piles of manuscript paper in the couple's Seattle home. Hovhaness's work is notable for its lack of the willful thorniness that defined the work of so many composers of his generation. Early on, he rejected the growing harmonic complexity of modern music in favor of a style that emphasized tonal -- more accurately, modal -- melody to create a sweeping, mystical atmosphere. An avid ethnomusicologist, Hovhaness delved deeply into his Armenian heritage and incorporated elements from Indian, Japanese and Korean traditions into his work. He was rewarded for his efforts by becoming one of the most frequently performed American composers. Yet despite his many admirers, Hovhaness's place in the modern canon, as the anniversary of his death approaches, is far from secure. ''Alan's music takes a lot of knocks,'' said Gil Rose, the artistic director of the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, which has performed several Hovhaness works. Indeed, much of the composer's work has met with scathing criticism. Douglas Watt, in a 1971 review for The New York Daily News, called Hovhaness's score for the American Ballet Theater's ''Rose for Miss Emily'' lifeless: ''the Hovhaness method here is to state a brief musical figure and then worry it to death by repetition.'' Ten years later, Alan Rich wrote in New York magazine that the oratorio ''Revelations of St. Paul'' was ''garbage, 75 minutes' worth,'' and lamented ''the travesties of the creative act perpetrated by the prolific Mr. Hovhaness.'' And no less an authority than Leonard Bernstein blasted Hovhaness's Symphony No. 1 (''Exile'') of 1937 as ''filthy ghetto music.'' What makes so many critics and musicians so uncomfortable about Hovhaness? The principal complaints are that his music is simple to the point of dimwittedness; that it is too New Age; that it never goes anywhere; that if you've heard one piece, you've heard 500." So far, I have listened to around 20 of his pieces with scores - either from the library or found online. Recordings are hard to come by - perhaps another ten scores I found at the library have no available recordings. I'm in search of records online and did buy a lot of 7 recordings that are conducted or played by the composer. I may put those up at some point. One of my favorite pieces happens to be mentioned in the article above, "Tzaikerk." Below is a performance:

2 Comments

I came across a set of pictures I took a few years ago - selfies in fact taken with a good friend of mine. I kept (and posted) the pictures despite the fact that she informed me - with her usual frankness (no brutality attached) - that I do not know how to take a selfie. For some, this may have been a point of shame, but for me this information was not unwelcome or surprising. I take pride in not being able to fulfill the obligations of pop culture acceptability. If a book is really popular, I avoid it. If everyone is watching a show, I wait until season 3 to start. (Let's not unpack this - maybe the easy explanation lies in how the "cool" kids treated certain types of boys. Maybe those certain types of boys did not want to be associated with anything "cool" after a time. Maybe.) One evening while enjoying tapas at one of my favorite restaurants with my then boyfriend and one of his coworkers who considered himself quite the proficient amateur photographer, this coworker kindly informed me that I must not be very photogenic - I'm too uptight and self-conscious. This was the first time I met him - the boyfriend made no attempt to defend me, what a joy. I took it personally - the more offended I became, the more closed-off and awkward I appeared, proving his point - much to his smug satisfaction. This was years ago now. I used to be mortified when someone told me I should smile more or asked me why I looked upset when I was just sitting there deep in my own thoughts. In her autobiography, "Offstage," Betty Comden (shown above) wrote that she received the same criticism from her children - she told them it's just the way her face looks, not a reflection of her emotional state. But it was when I read these lyrics by Ani Difranco from "Evolve" that I began to reconcile myself to my own visage and appearance: "I walk like I'm on a mission 'cause that's the way I groove I got more and more to do I got less and less to prove It took me too long to realize That I don't take good pictures 'cause I have the kind of beauty That moves" Image has become more important than ever for the artist in the age of selfies. Universities and conservatories offer classes in how to brand yourself (we are now cattle - moo! - branding ourselves - ouch!). I have been in casting meetings for shows where the decision to hire someone has hinged on the number of Instagram follows he/she has. If you browse through the suggestions on Instagram, you will likely find members with hundreds of thousands of followers - on their page will be an array of selfies - no other content to speak of, perhaps an ad disguised as a selfie or a picture with someone else who will equally promote them. If you go a step further and study the gay versions of these self-aggrandizing profiles, body image becomes even more paramount. Young or old, a six-pack is required (unless bulking, duh) to enter into these treasured existences of monthly Mykonos vacations, protein shakes, and parties where the only necessities are tiny shorts, mobile phones (for selfies), and little blue pills (or whatever color is currently popular - I'm sure there's a rainbow array of choices). And what does this image represent? These gym (and steroid) produced bodies? Health? Athleticism? Or just look like these things? Image, image, image. As Edina says on Ab Fab while perusing several magazines in order to choose a kitchen design (to replace the one Patsy burnt down) - "I want people to think I'm ALL these things." To be our most happy (gay) selves, we must pretend to be the image of masculinity we developed in our formative years. Childish boys dancing around in packs of lookalikes pretending to be the men they always wanted to me. But then we're used to pretending aren't we? Even dancers in theatre - thanks to social media and, if I may say, certain fundraising efforts aimed at exploiting the bodies (and the lust for the bodies) of such dancers - even these actual athletes have changed the way they approach fitness in order to conform to this overinflated anti-effeminate, muscle-bound model of masculinity - to the point where one wonders how they can pirouette at all without falling forward for the weight of the pectoral mounds. My own Instagram is filled mostly with objects or places I encounter along the way through life. I'm not sure I have even one selfie in the mix. At some point I need to get headshots for my career - how I've avoided it so far must be no mistake and related directly to my own self-consciousness (see the above story - he will NOT be taking the photographs). I used to say I don't show up on film when someone wanted to take my picture - but with digital photography, that pretense loses its modicum of veracity (let alone humor). I'll leave you with Ani to enjoy below. As always with her songs, more than pop songs, listen to the words! The scene above is of course from Lewis Carroll's 1871 book, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. Alice has just helped a disheveled White Queen with her disobedient shawl and her unruly hair, and the queen has proposed taking on Alice as a lady's-maid. When offered jam on any day except to-day, Alice becomes befuddled by the queen's seeming illogicality but (in my favorite line) the queen assures Alice that her confusion comes as a natural result of living backwards - and in fact can make one "a little giddy." (Giddy denotes a feeling of disoriented excitement but literally means possessed by a god.) I've been thinking about this section of the book for the past few years as I wrestled with my acceptance, banishment, and (healthier?) re-introduction to the numerous and sundry social media platforms. Confronted daily with the frowning zombies staring into their own palms while thumbing through thousands of digital pictures, twitter feeds, or facebook pages on the subway, at a restaurant, in a car, walking down the street (into traffic), etc., (LOOK UP!!) I have assumed something of a hobby-study: deciphering what kind of joy these "users" believe they feel in this catatonic state. In what timeline are they experiencing the joy? Is it in the future when the friend, whose picture they "liked," "likes" theirs back as a reciprocal act? Is it in celebration with their past-self friend - as if double tapping a picture is anything more than a fleeting gesture, saying: what a great, staged moment that was? (Remember when you dreaded sitting through a slideshow of holiday snapshots?) And what of the poster? Are they capturing this well-lit, overly overjoyed version of themselves eating a taco with the love of their lives (#blessed) for the joys of the future "likes?" Or to "remember" the moment for the self-congratulatory euphoria they feel when flipping through thousands of their own digital pictures on the subway, at a restaurant, in a car, walking down the street, etc. etc.? Celebrating a false past, never experienced only OBSERVED? How do we live in the now? Can now be experienced or is it such a minuscule cross-section of time that one can never be in it but only on either side of it? How far away from now can we experience the now and still be in the now? Actors in the theatre are taught to "live in the now" while onstage, to experience the character's reality in each moment. As a conductor in the theatre, I have to be attuned to the present in order to keep the many individuals in concert with each other during a performance. My piano teacher used to reprimand me for restarting a moment if I made a mistake - I've learned to experience the mistake and continue, but that took years of playing to achieve. How many times have you been to a wedding and witnessed as attendees watch the bride's procession through a screen? How about a concert? Or a party? We have always learned from the past. We've read stories from the past. Attended plays from the past. And looked at pictures from the past. But that is not what is happening in social media use and consumption. When someone photographically captures(!) an experience in order to relive it later, they have stepped through the looking glass and into a temporal quagmire. In order to re-live an experience, one must live it first. While collecting the information through the filter of a device, the moment that should have been experienced has instead been viewed - in the same manner in which that person intends to consume the material later. If you have never experienced the life moments you record, how can these posts be a reflection of you? We share experiences we have never experienced. You live on either side of the picture - but suspend an artificial representation of yourself (or your experience) in between. You wait to see how many viewers you get, how many likes, how many retweets. You celebrate your past self, who is not really you because you were never doing the deed you captured, only posing or demonstrating the behavior - perhaps redoing the shot many times to get the perfect angle and lighting. You wait to find out the worth of your future self, existing through the acknowledgement, acceptance, and virtual love from others. Is this how we must live now? Tree in the forest living. If no one likes my picture, did the event happen? I've considered not putting this out - these are just my initial thoughts on a much larger societal shift in how humans "interact." I used to think people were living in the past on their phones - but now I think it's both the past and the future. At any rate, click below and please enjoy Carol Channing singing "Jam Tomorrow" from the 1985 TV mini series version of Alice in Wonderland - songs written by Steve Allen. If you have been watching Marie Kondo on Netflix, which I assume you have, then you are familiar with her style of organization for our age of consumerism. Maybe you've chuckled a bit when she knelt down to greet the home or when she insists that one must touch every item to "spark joy" and if no such spark occurs one should thank the item before discarding it. Or maybe you have realized that in an age where plastic is destroying the oceans, taking the time to respect and familiarize yourself with every belonging you own is not such a ludicrous idea. After listening to several newish orchestral works (premiered in the last 5 or 6 years), none of which I will name here (you can DM for details, if you are really interested - maybe you'll have a completely different experience with the pieces than I did), I believe we composers can benefit from KonMari. I usually refer to this type of writing as "kitchen sink" composition because everything is crammed into the mix, sometimes in a more artful way than others. So much clutter! Have you touched every note and asked if it sparked joy? (My other least favorite style is "orchestra tuning" music where we are forced to sit through 7 minutes of sliding sonorities and timbral changes.) I have listened to at least five orchestral works this week that use the same formula: 1) provide a hook for the audience. This can manifest itself in several forms: a "jazzy" introduction or conclusion (a concluding hook is especially desirable so everyone can chuckle at the end in the most erudite manner, be in on the joke, and say things like: why does classical music have to be so serious??), a reference to pop culture in some musical form, perhaps littered throughout the piece (if you can quote, Björk, Radiohead, or the Beatles you win), or to cater to the crowd: quotations from other classical works thrown into the last (shortest and fastest) movement as "whimsy" - not to add significance to the piece. 2) no recurring ideas God forbid - are you even creative, bro? 3) no one plays anything similar at the same time If (I stress if) instruments happen to play anything remotely similar at the same time, there must be some metric irregularity. Also, the more notes and varieties of rhythm that can be layered, the better the craftsmanship. Seriously, tuplets, tuplets, and more tuplets. All of these: irrational rhythm or groupings, artificial division or groupings, abnormal divisions, irregular rhythm, gruppetto, extra-metric groupings, or contrametric rhythm (from the Wikipedia article on tuplets!). Odd numbers are best. 11's or 17's? They will definitely be accurately played. 4) every note MUST have some kind of articulation and a dynamic marking. Players cannot be trusted to interpret. Leave nothing to chance! And if an instrument uses vibrato, you should specify when and how that vibrato is used. At all times. Ex. over ONE quarter note: vib.-->non vib.-->quasi vib.--->molto vib --> ord. vib. 5) satire At first, make it seem like you are composing a piece that humorously comments on the more cliché practices of modern composers, then stretch that out for 17 minutes until the audience realizes it has been duped. Just as they begin to despise the piece (and you), add in a non sequitur quotation or "jazzy" section (see no. 1) to gain back their trust. Then, continue what you intended to write. The audience may turn on you again but as long as you end with something tongue and cheek (again see no. 1), no one will mind the 16 minutes of squirming and secretly checking their phones. Ok, enough burning bridges. Why don't you click on these links and see which sparks joy:

Recently, I have begun going through the archives of Berlin Philharmonic concerts - highly recommended for concerts at home, live or recorded. (www.digitalconcerthall.com/en/news) Mostly I have been exploring the 20th and 21st century repertoire that I don't know with score in hand - a lot of scores are available online through the publishers as perusal scores, some you can even download, which I prefer so I can use them on my iPad. I'm happy to report that the Berlin archives have a healthy amount of rep from the last 100 years and ashamed to admit that I have heard a scant number of what they offer. Putting shame aside, I have in earnest (thank you, New Year's resolutions) set to work listening to/watching a couple of hours worth of these pieces a day. (I should say that I am [for now] skipping over much of the standard rep composers such as Ravel or Shostakovich in favor of getting to know the orchestral music of Chin or Haas better.) I started at the letter "A" on the archive list not only as an admittance of my own quotidian nature but also because two of my favorite composers were included with that letter: Abrahamsen (Three Pieces for Orchestra and Let me tell you) and Adès (Asyla, Powder Her Face: Dances, and Three Studies from Couperin). The A's also contained pieces by Samuel Adler, Julian Anderson, George Antheil, and Richard Ayres (his NONcerto for horn and large orchestra which I skipped because I am in search of a score). After the A's, to reconcile my commonplace alphabetical beginning, I jumped to the Z's. So far at the end of the alphabet, I have been focusing on one composer whose music spoke to me in ways I have not yet begun to articulate: Bernd Alois Zimmermann. Why have I not gotten to know this composer before this year? Too much rep, not enough time. And that is what this trek through the archives is all about. Berlin has six of Zimmermann's works in the archives: Symphony in One Movement, Alagoana, Canto di speranza, Photoptosis, Violin Concerto, and Requiem for a Young Poet. The last piece I have not heard yet because I need to sit in the NYPL reference section in order to listen with the score. Many scores of his work are available through the publisher Schott - if the score has a "Preview" banner on the cover, you can click on it to see (and download for further study) the full score. If I could not find the scores online, I looked for them through the library or interlibrary loan (although most libraries are wont to lend scores out for some reason likely quantified monetarily - insert eye roll emoji ). Today, I listened to (along with Bernstein's Divertimento and Martinu's Violin Concerto no. 1 - see, I'm jumping around the alphabet a bit) two pieces by Zimmermann: Canto di speranza and Photoptosis. In the latter, Photoptosis ("Incidence of Light") , Zimmermann makes use of musical quotation from Beethoven, Bach, Scriabin, Wagner, and Tchaikovsky layered over each other and emerging from a sonorous orchestral texture inspired by an Yves Klein painting for the Gelsenkirchen music theatre. The orchestral representation of light captured by Zimmermann mesmerizes the listener. As conductor Hannu Lintu said: "Zimmermann’s music is exceptionally rich in colour. I can see and hear in it a musical synthesis of colours and lights, like continuing from where the Impressionists and Scriabin left off. Photoptosis is a study of the way sounds and motifs change when they are instrumented in different ways." The quotations feel like a part of the light play, as if one is seeing (hearing) the work from a different angle and a flash of music suddenly appears. (Listen here or buy here) The use of musical quotation reminded me of another piece (not Berio's Sinfonia but good guess, love that piece): Prism by Jacob Druckman. In this three movement work for orchestra, Druckman explores the myth of Jason and Medea as seen through the music of Charpentier (Médée), Cavalli (Il Giasone), and Cherubini (Médée) - looking as Druckman said both forward and backward. In the first movement (Charpentier), the quotations pop up as surprises, leaping into being and playfully usurping command of the piece, if only for a few bars, then disappearing again. The second movement (Cavalli) gives the impression that Medea is a wax figurine melting in front of our eyes (ears). The musical quotations hover in the background, as if heard through a thick, wooden door or floating on the air a great distance away. Cherubini's music confronts the listener in the final movement with violent jabs and caustic taunting. The orchestration of the movement feels more akin to Mahler with massive waves of sound overtaking ones senses between chamber music-like instrumental solos. Allusions to war: guns firing, marching, and brass fanfares abound. (Listen here) Perhaps as Lintu said: "Music [of the late 20th century] was in transition, and the cupboard was bare: composers felt a need to look back over the whole history of music, and especially the stylistic trends of the 20th century – its pared-down, endlessly theorised musical phenomena, modern simply for the sake of it." Both of these works use light as inspiration through which to view the work of other artists - with Zimmermann the lens is more open and the picture blurry while Druckman focuses in on specific subjects. Interestingly, both pieces end abruptly, just as light has no discernible ending point. Below, Druckman discusses his compositional process. I've never worked that way: writing out a few pages of ideas for the instruments I have available and then seeing if any of them connect. Worth a try. I love how he laughs off agonizing over writing. Oh, and the dog story... You can see a perusal score for Prism using the link below. You need Flash, FYI, and cannot download the score.

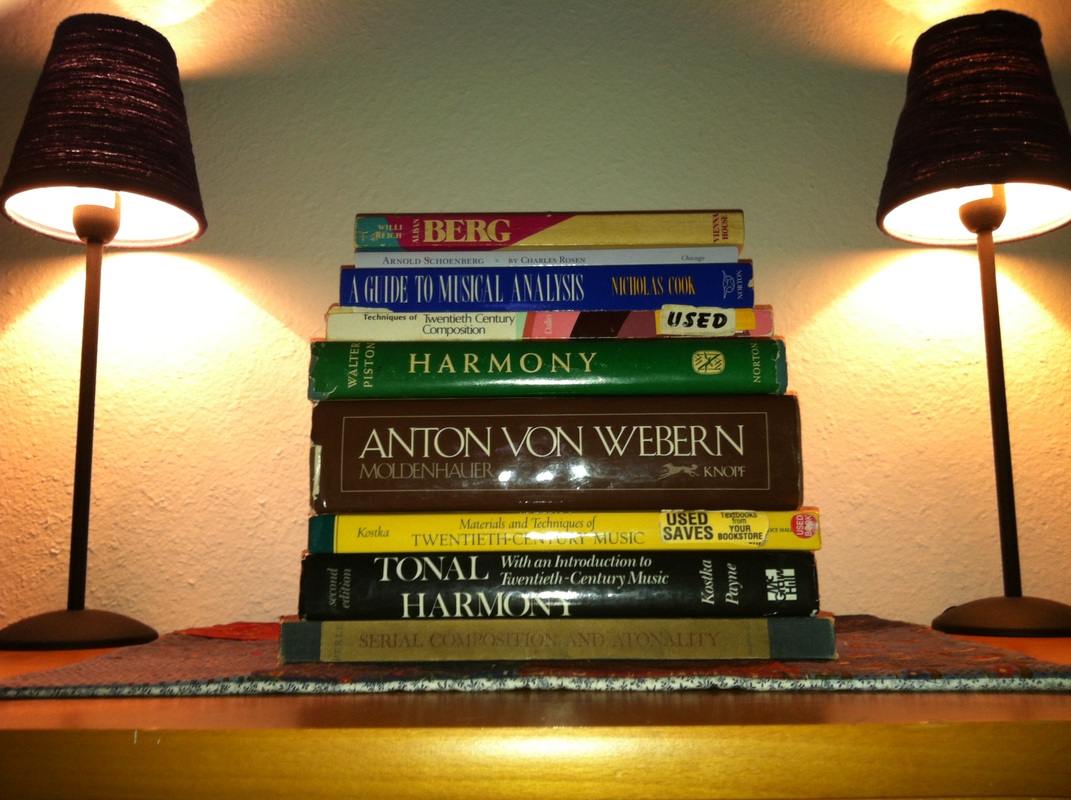

www.boosey.com/cr/perusals/score?id=1090 NY Times review of Prism here. Also an article on light in Druckman's music here. To see a score for Photoptosis, I borrowed through Interlibrary loan through the New York Public Library. No, it is not just the fabulous hair, stern look, and hip glasses. As I have studied the music and lives of the Second-Viennese-School composers over the past month, I have been pleasantly surprised by a few discoveries. The first being: Schoenberg writes expansive and lyrical vocal lines! Listening to his early songs (especially with orchestra) or even his Pelleas und Melisande, one can easily mistake the work for that of Richard Strauss. The sweep, the grandness, and the (heavy) orchestration all speak to the links between Schoenberg/Strauss and Wagner/Beethoven, the apparent, direct lineage. This week, I have been focussing on Webern, however: reading the 800-page biography by Hans Moldenhauer. (Quite the tome to tote around. And I have been accused of reading a Harry Potter book. Excusez-moi?) As it turns out, Webern's experiences (and travails) as a composer, seem to mirror my own. And , while I am struggling at the moment to keep myself positive with regard to a career in composition and forcing myself to acknowledge the bigger picture rather than fretting over minutiae, I take comfort in the fact that another composer, whose music I revere, struggled as much. Below are some quotes and interesting parallels between our lives: First, Webern issues the same complaint in 1902 that I hear many of my colleagues declare today: "Now the concert season roars with terrible force! Mostly miserable programmes [sic]! Every concert over-crowded with people who applaud after each number, not caring whether it is good or bad. Probably, nay certainly, the people can no longer perceive any difference. Their taste is continually corrupted by miserable programmes and witchcraft virtuosi." Ok, I definitely felt this at a recent concert that I thought was good, but did not warrant the sudden, almost violent, thrust to a standing ovation (those older patrons are surprisingly agile) at the end of every piece. I feel no obligation to stand - and I can withstand glares, from young and old, so save them for someone else. Now, who knew that Webern worked in the theatre? Not I! Here are some of his reflections on these jobs. I've said or thought all of them at one point or another. "My activities have been horrible. I find no words to describe such a theatre. May the world be rid of such trash! What benefit would be done to mankind if all operettas, farces, and folk-plays were destroyed. Then it would no longer occur to anyone that such 'art work' had to be produced at any price. It is enough to drive one mad." PREACH "Mahler remark[ed] that I should not go to theatre since I would not find time to compose. I cannot get this out of my head anymore." Thanks, Gus. Words of wisdom. "I would flee a theatre such as the one where I am at present as if it were a place infested with the plague, and now I myself must help to stir the sauce. Often I am ashamed, I appear to myself like a criminal even collaborating in this hell-hole of mankind. I can hardly await my deliverance from this morass." Speaking of the necessity to work at such jobs while neglecting his writing he said: "I maintain almost unshakably the stand of wanting to dedicate my work exclusively to my compositions. I could entirely forswear every worldly position. If I could only halfway find subsistence in any kind of job that does not take me away from composition, wholly and completely, for months on end. As it is, one must kill off what wants to come forth. This is the difficulty, and it makes me very unhappy." (Disclaimer: This does not reflect my personal feeling about EVERY theatre job I have undertaken. If you are reading this, I am NOT talking about you.)  As I get (ahem) older, I become more and more aware of the gulf between my age (as if I would ever reveal my REAL age) and the ages of my colleagues who are at the same stage in career as I. Here are some of Webern's similar reactions: Regarding Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who shot to stardom at age 13(!): "Publishers, performances–the boy has everything. I will become old before that." Webern was 27 at the time. The next year, while working in the theatre, Webern again felt despondent: "Am I thus to spend all my years–feeling redeemed each evening that another day has passed? Does this make any sense? I am growing old and am nothing and have nothing and accomplish nothing, or better, cannot accomplish anything." Yep, I think I have said something similar weekly for the past...well, a lot of years. I have been entering a TON of contests and commissioning competitions over the past three years. With almost no success. Some second places. Mostly no word at all. They take the $100 entry fee (plus the exorbitant cost to print, bind, and ship a score) and run! Ah well. I'll leave you with Webern's Five Sacred Songs, op. 15, which he sent into the Berkshire Chamber Music Composition Contest in 1924 and LOST! Didn't even place. Who won? I guess that is something to research. Continuing my study for the month. I have my first comp exam (theory) on April 14th! (Send me some good vibes, please!) And I plan to take a second comp exam in June - so I am double-duty studying! Yay! Actually, I am rather enjoying myself. Going back to the basics, reviewing, and working my way back to and beyond where I am in terms of knowledge is how I like to study. Below is a picture of the books I am reading this month. (Some of which I have read and studied many times before, so stop judging me for these basic theory books - it's called review, ya'll.) Of course, all of this is supplemented with score study and listening. Still delving into the 2nd Viennese School oeuvre. Finished my initial study of Berg. Moved to Schoenberg this week (the order of study was based on when the biographies I ordered came in the mail). Please note, the Charles Rosen book on Schoenberg (under Willi Reich's book on Berg) is 100 pages, while the Anton von Webern bio is almost 800. Oh my. And this week for theory - I need to practice writing fugue expositions again! Gotta go dig out my notes. In order of appearance: Alban Berg - Willi Reich Arnold Schoenberg - Charles Rosen A Guide to Musical Analysis - Nicholas Cook Techniques of Twentieth Century Composition - Leon Dallin Harmony - Walter Piston Anton von Webern - Hans Moldenhauer Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music - Stefan Kostka Tonal Harmony - Stefan Kostka and Dorothy Payne Serial Composition and Atonality - George Perle I'll leave you with three Schoenberg pieces, in which he began to use serial techniques. 5 Pieces for Piano, op. 23 (1920/23) - Considered the first use of serial technique. Without getting into detail, the last movement (the waltz) uses a 12 note motif as the melody, with everything else derived from this "series." Charles Rosen: "There is one revolutionary aspect about this piece...except at the beginning [of the waltz], the order of the twelve notes is not a melody, but a quarry for melodies; the melodic line may at times start in the middle of one presentation of the set and continue part of the way into the next...The phrases are broken without regard to the twelve-note set, which has an identifiable shape of its own only the first time it is played." Serenade, op. 24 (1920-23) - The fourth movement, a Petrarch Sonnet sung by bass-baritone, uses the 12-tone technique. The singer repeats the same set of pitches throughout the piece, but, since the lines of the Sonnet are 11 syllables long, "each successive verse begins one note earlier." This is the longest piece of the three and probably my favorite. I love the instrumentation (Clarinet, Bass Clarinet, Mandoline, Guitar, Violin, Viola, Cello), and the quaintness and character of each movement. Suite for Piano, op. 25 (1921/23) - This piece is definitely serial. Schoenberg uses one set for the entire piece (6 movements), to unify. You can look up the series and its derivations online. Very symmetrical with the use of the tritone, and references Bach's name in the last 4 notes. Pieces like this are when you go: oh, yeah, genius. Please note that in each of these three works, Schoenberg adopts musical forms and genres from the past, as a sort of reference point. Definitely not free-form, "anything goes" works. And also not cold, unfeeling pieces. Character abounds! If one studies these three pieces with the "image" (sound-image? there must be a German word for that) of the older forms (Minuet, Gavotte, etc.) in mind, the fact that they are "freely" atonal or serial feels almost inconsequential. In fact, I find that, free from the constraints of the tonic-dominant relationship and the "tyranny of the octave," as Charles Rosen calls it, the character of each movement (dance form, etc.) comes through with a heightened clarity. (PS - the 5 seconds you have to wait to skip the ad at the beginning is SO worth it - love this recording!) I began studying Schoenberg's vocal music a couple of days ago (again, for a comprehensive exam). Along with lots of listening, score study, and poring over journal articles, I have been reading Charles Rosen's slim volume, Arnold Schoenberg. Here are a few interesting tidbits and insights into one of the most revered and reviled figures of 20th century music composition. Of the string sextet, Verklaerte Nacht, a contemporary of Schoenberg said: "It sounds as if someone had smeared the score of Tristan while it was still wet." Oh my. How about this Richard Strauss v. Schoenberg action: Strauss, 1913: "Only a psychiatrist can help poor Schoenberg now...He would do better to shovel snow instead of scribbling on music paper." Schoenberg on the occasion of Strauss' 50th birthday: "He is no longer of the slightest artistic interest to me, and whatever I may once have learned from him, I am thankful to say I misunderstood." Yikes. Another Strauss TidbiT from Charles Rosen: "Strauss is known to have been disconcerted [haha- good one, Charles] by the growing virtuosity of modern orchestras and their ability to give an unfortunate clarity to passages written to sound as a sweeping and harmonious blur." Reminds me of some of the chorales from Bach's St. Matthew Passion, which would have sounded more dissonant in his tuning system.  by Charles Rosen "A dissonance is any musical sound that must be resolved; a consonance is a musical sound that needs to no resolution." Thanks, Charles.

"If dissonance is understood as that which demands resolution (and this definition must be maintained if the expressive role of dissonance in the language of musical representation is to be understood), if it has meaning only as part of an opposition consonance-dissonance, then the elimination of consonance, of resolution, destroys the basis for expression, makes dissonance itself meaningless. The powerful emotional force of Schoenberg's music would then be intelligible only against an inherited background of traditional harmony, and would itself be an incoherent system, dependent on a musical culture it was intent on destroying." Oh, the irony. More Berg - study, study! As I am writing my own opera (only a 1/2 hour left to complete!), struggling to finish while I daydream about an actual production of the piece, these stories about Berg (all taken from Willi Reich's book Alban Berg) help me to stay focused and hopeful. In 1922, after completing the score for Wozzeck, Berg attempted to sell copies of the vocal score to make some money. The pages of the score numbered 230 and the cost came to 150,000 Austrian Kronen (20 Swiss Francs). Berg sent one of his pupils out with the statement: "Art looks for Bread," soliciting patrons of the arts to buy a copy. "The production [of the score] was enormously expensive and I'll never be able to persuade a publisher to pay for it, so I would like to sell a number of them beforehand for my own account." Self publishing! One of his students said: "No publisher even thought of publishing the monster; the vocal score was in hot demand only amongst his good friends, and they got it free." Oops. In terms of the experience of opera, particularly Wozzeck, Berg believed that the audience should have no idea of form and structure from hearing the piece, rather they should be swept up into the story: "From the moment the curtain rises until it descends for the last time, there must not be anyone in the audience who notices anything of these various fugues and inventions, suite movements and sonata movements, variations and passacaglias. Nobody must be filled with anything else except the idea of the opera–which goes far beyond the individual fate of Wozzeck." Drama, drama, drama! Would Berg have disagreed with the above pre-concert lecture? Hm, I doubt it. Of Bruckner's music (as well as Mahler and Wagner) he said: "Even Bruckner–who had been dead some years–was a long way from being 'generally recognized' or 'arrived' as one calls it. Societies had to be founded to bring his work within reach of the world's understanding. These societies considered it their business to make propaganda, as we call it today: introductory lectures, and performances of his symphonies in four-hand reductions...all this was necessary for Bruckner at the time."  Anton Bruckner (1842-1896) Below is the Wozzeck I am currently listening to - but on LP, yes, a real vinyl recording! Love. Finding a libretto and scene by scene musical analysis is easy online. I think the translation of the German (if you don't speak the language) is especially important to understanding Berg's musical choices. Enjoy! Patrick and Gloria, pictured above, are looking askance at me because they never believed (and neither did I frankly) that I would write a blog. (If you have no idea from where this movie still originates, I am sorry to hear that and I wish you good day). As I write this first post, I am not sipping on a Flaming Mamie as are they, but a delicious G&T with a twist of lime. We need to start of right, after all. No intro. Just jumping in. Reading about Berg Lieder recently, studying for an upcoming comprehensive exam. Somehow, I never realized how meager Berg's output really was. Although Berg had written quite a number of songs before working with Schoenberg (which began around 1904), his Opus 1 Piano Sonata was his first published work in 1910. Wozzeck, begun in 1914 and completed in 1922, was given the opus number of 7! As Willi Reich relates, "[Berg] later abandoned opus numbers for this and all succeeding works. His jocular reason for this was that he was ashamed of having produced so few works in such a long period of time." Oh, Berg, I can relate on that point. Actually, I am pre-opus number at this point. Of course, in the days of self-publication, do opus numbers carry the same significance? Berg died in 1935, with a small but significant output of music. Really, check it all out. Having listened to all of Berg's songs, minus the 50 or so Jugendlieder, one finds his mathematical precision matched with the passion and lyricism found in his vocal lines. Berg's first foray into atonality lies in one of his songs, "Warum die Lüfte," the fourth and final song of his opus 2 collection. And his first use of 12-tone technique is found in his second setting of "Schliesse mire die Augen beide." Another favorite of mine is Altenburglieder (op. 4) for mezzo soprano and orchestra. Please delve into the clips below. Scores are available here: 4 Gesänge, Op.2 5 Orchesterlieder, Op. 4 (Altenberglieder) |

Andrew Haile AustinA record of events, a log of compositional progress, Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed